This week is National Rip Current Awareness Week, so our concierge doctors in Jupiter want to acquaint you with this common, often-deadly, phenomenon. The National Weather Service (NWS) has already reported 17 surf zone fatalities nationwide this year, including one in Jupiter, and another nearby, from rip currents. The beach, while beautiful, needs to be approached respectfully.

An average of 100 people die in rip currents every year, and nearly 80 percent of all rescues—30,000 a year—made by lifeguards at ocean beaches are from rip currents. Although they can occur at any time, they are especially prevalent when the ocean is churned up with powerful offshore storms.

But bad weather is not necessarily a requirement for developing a rip current. Great weather for the beach does not always mean it’s safe to swim, or even to play in the shallows. Rip currents often form on calm, sunny days.

What is a rip current?

Rip currents are often incorrectly called “rip tides.” A tide is something different: a very gradual change in the level of water, occurring on a regular basis over a period of hours.

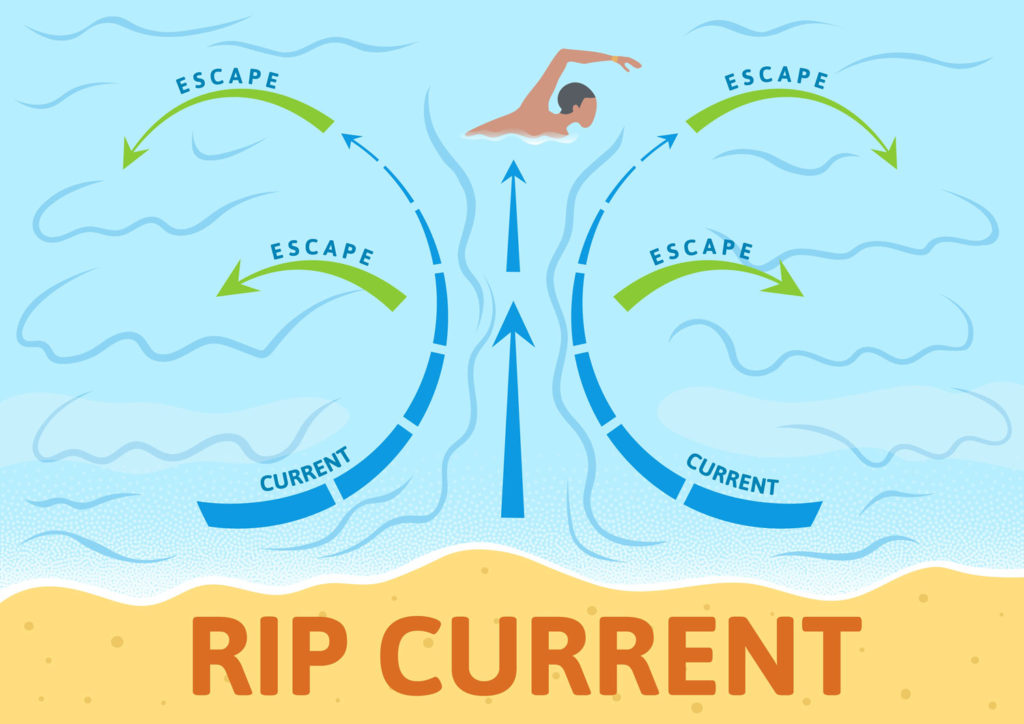

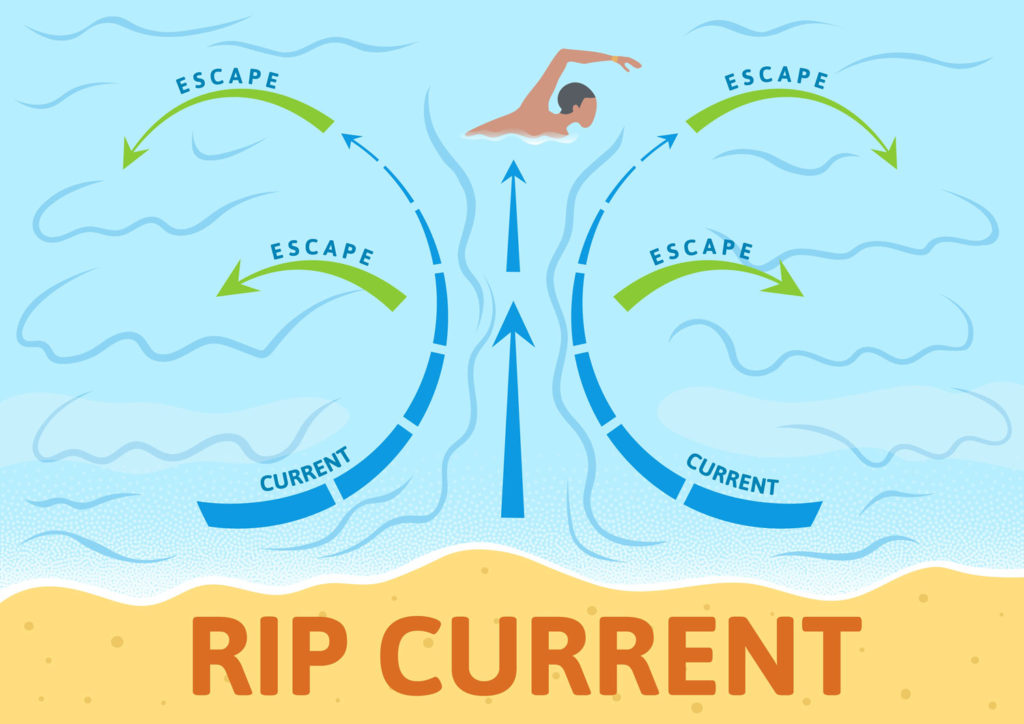

A rip current is a powerful, narrow channel of fast-moving water that can rush at speeds of up to eight feet per second, pulling swimmers away from the shore out into open water. They usually extend through the line of breaking waves, but can flow a hundred yards or more offshore. They can be as narrow as 20 feet or as broad as several hundred yards wide.

Often referred to as “undertow,” rip currents don’t actually pull swimmers under the water. The strongest pull is actually felt about a foot above the bottom of the ocean’s floor, which can knock your feet out from under you, making you feel you’re being pulled under, even though you’re not. But because of the current’s power, as the shoreline rapidly recedes, swimmers panic, struggle, exhaust themselves, and drown.

How to spot a rip current

Rip currents are most prevalent at low tide, when the water is already receding from the beach. They are also more likely to occur with a strong onshore wind.

Though often difficult to discern from the shore, some of the telltale signs are:

- an area with a noticeable difference in the color of the water, caused by sand and sediment being churned up by the water;

- a line of foam, seaweed, or debris moving out to sea; or

- a place where the waves aren’t breaking, but has breaking waves on either side.

Remember, though, that many rip currents are completely invisible. The only time you can be certain there are no rip currents hidden in the water is if there are no breaking waves. No waves, no rip.

How to ‘Break the Grip of the Rip’

The U.S. Lifesaving Association (USLA) warns that not even Olympic swimmers can swim against a rip current, because the pull is simply too powerful. According to the USLA, the most important thing to do when caught in a rip current is to remain calm. This helps you conserve energy and think clearly. Realize that you will not be pulled indefinitely out to sea; remember that most rip currents dissipate within a hundred yards of shore.

The U.S. Lifesaving Association (USLA) warns that not even Olympic swimmers can swim against a rip current, because the pull is simply too powerful. According to the USLA, the most important thing to do when caught in a rip current is to remain calm. This helps you conserve energy and think clearly. Realize that you will not be pulled indefinitely out to sea; remember that most rip currents dissipate within a hundred yards of shore.

- Don’t fight the current. Swim out of the current in a direction following (that is, parallel to) the shoreline. Once you’re out of the current’s pull, swim at an angle through the waves back to shore.

- If for some reason you can’t reach shore, draw attention to yourself: Face the shore, wave your arms, and yell for help.

- If you see someone in trouble, get help from a lifeguard. If one is not available, call 911. Throw the victim something that floats and yell instructions on how to escape. Remember, many people drown while trying to save someone else from a rip current.

Finally, never swim at a beach without a lifeguard nearby. The USLA reports that the chances of drowning at a beach with a lifeguard are 1 in 18 million.

If you have concerns or questions about this or any other health-related topic, please feel free to contact us.

The U.S. Lifesaving Association (USLA) warns that not even Olympic swimmers can swim against a rip current, because the pull is simply too powerful. According to the USLA, the most important thing to do when caught in a rip current is to remain calm. This helps you conserve energy and think clearly. Realize that you will not be pulled indefinitely out to sea; remember that most rip currents dissipate within a hundred yards of shore.

The U.S. Lifesaving Association (USLA) warns that not even Olympic swimmers can swim against a rip current, because the pull is simply too powerful. According to the USLA, the most important thing to do when caught in a rip current is to remain calm. This helps you conserve energy and think clearly. Realize that you will not be pulled indefinitely out to sea; remember that most rip currents dissipate within a hundred yards of shore.